Responding to Covid-19 in Delhi

India announced a nationwide lockdown on March 24, 2020 to restrain the imminent spread of the novel COVID-19 virus across the country. Thousands of migrant workers and laborers in cities rushed to bus stops and train stations to find a way back home. The government shutdown shuttered transportation facilities, stranding the migrant workforce without food and shelter.

Immediately after the lockdown announcement, Rajesh Veeraraghavan, an assistant professor in the Science, Technology and International Affairs program in the School of Foreign Service and participating faculty member of the Georgetown Global Cities Initiative, worked with researcher Hridbijoy Chakraborty to use the Urban Spatial Observatory’s (USO) dataset on public services with a focus on access in informal settlements as the framework for their first COVID-19 map, published on Twitter as #DelhiHungerReliefCentre.

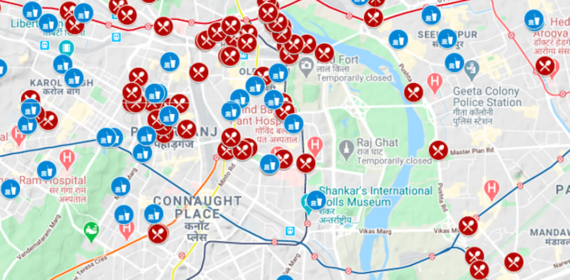

This map of Delhi included the locations of night shelters, ration shops where poor people can buy groceries at subsidized rates, and identified 427 schools functioning as hunger relief centers. The USO team worked together with the Delhi government’s COVID relief team and other researchers, particularly Gautam Bhan of Indian Institute of Human Settlements and Parushya of LEAD (Leveraging Evidence for Access and Development) at Krea University to create simple, dynamic, accessible maps to guide people to their nearby Hunger Relief Centres and temporary shelters for migrant workers.

In a testament to the map’s accuracy and utility, Delhi’s government added the USO map to their coronavirus response page. The map was shared on Google’s My Maps platform, Open Street Map (OSM), and Map My India’s COVID response map. It was also by several media outlets including Hindustan Times, Indian Express, and IndiaToday.

Mapping Hunger Relief Centers in Real Time

During the initial two days of the lockdown, 231 night shelters for the homeless were also serving as hunger relief centers. The shelters, particularly those near interstate bus and railway stations, were quickly overcrowded. Some homeless people were also shifting from more peripheral areas of the city towards the center for safety, as the area around Old Delhi has been a safe space for homeless people. To maintain social distancing, the Urban Spatial Observatory researchers worked with the Delhi state officials to use data they had collected on schools to locate alternate locations for additional shelters and coordinated with the government to establish new hunger relief centers nearby.

As part of its response, the Delhi government launched a hunger helpline in each of its 11 administrative districts to address increasing demand for food and rations. The Delhi based team lead of the Urban Spatial Observatory, Hridbijoy Chakraborty, created an internal map for use by officers and volunteers and consulted with the Delhi Disaster Management Authority to design a map protocol for helpline operators, who were trained to use the map to identify food request locations and connect people to their nearest relief center. Operators could also flag a nearby public facility where an additional relief center could be added.

Throughout this process researchers identified and mapped 650 relief centers, helping citizens, relief volunteers, social workers, and government officials get access to reliable information on their mobile phones. These maps continue to be updated regularly and are being shared through Twitter, Whatsapp, and through a dedicated website.

Expanding Access Through Data

The observatory’s COVID-19 response maps exemplify USO’s goal of using socio-spatial data to create more equitable, accessible, and livable cities.

The Observatory was launched in collaboration with Patrick Heller, from Brown University, who had led the cities of Delhi project. The cities of Delhi project found that though Delhi’s informal settlements house a majority of the city’s residents, they are often rendered invisible in official data and thereby excluded from public services available to formally planned areas. The observatory’s team is working to build data on access to public services using satellite imaging, machine learning, ethnographic fieldwork, and community participation. In addition to spatially documenting the differentiated citizenship and fragmented cities experienced by the poor, the observatory also works with partners on the ground to turn data into useful resources for public information and actionable policy insights for citizens, governments, NGOs, and activists.

The Urban Spatial Observatory is an interdisciplinary research group with faculty, students, and researchers from Georgetown University, Brown University, Center for Policy Research, Hyderabad Urban Lab and Indian Institute for Human Settlements. In addition to Rajesh Veeraraghavan, Hridbijoy Chakraborty, Bob Bell, and graduate of Georgetown's Urban & Regional Planning Program Shubhada Varde (G-URP’19) and Sky Colloredo-Mansfeld (SFS’19) –a Fulbright-Nehru Research Fellow– are all actively working to build these maps.