Exploring the Spiritual in Cities

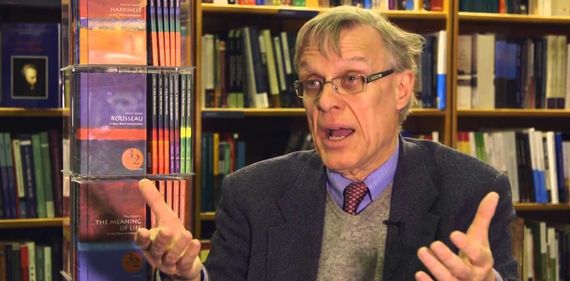

Reflections on a week with Professor Philip Sheldrake, the inaugural visiting fellow of the Georgetown Global Cities Initiative. Prof. Sheldrake is a Christian theologian, inter-faith activist, and trained Jesuit, whose most recent book is: The Spiritual City (Wiley Blackwell, 2014)

By Chrystie Flournoy Swiney

The Georgetown Global Cities Initiative (GGCI) hosted Professor Philip Sheldrake, the Initiative’s inaugural visiting fellow, for a series of student workshops and faculty roundtables the week of November 5th, 2018. Sheldrake, who originally trained as a Jesuit, is now a scholar of cities and spirituality, a renown Christian theologian, an inter-faith activist, an author of over a dozen books, essays, and an intellectual who thinks deeply about the nature and meaning of “place”, especially in the context of the city.

Sheldrake studied history, theology and philosophy at the Universities of Oxford and London, and has taught courses at Heythrop College, University of London, Durham University, Boston College, Cambridge, and elsewhere. In his most recent book, The Spiritual City, Sheldrake explores the meaning of the sacred in the spatial context of the city. He advances the idea that the city itself should be conceptualized as a sacred space, one that must be shaped and formed by the people that inhabit it, as opposed to a top-down, exclusively elite-driven and financially-motivated process.

For Sheldrake, the city is not the steel, asphalt, fumes, and high-rises that materially comprise it, but instead, the subtle, almost imperceptible, and mundane, yet meaningful, encounters and interactions that occur among its people and the communities they form. In Sheldrake’s view, cities are “walked into existence” by its inhabitants, whose shared experiences and memories infuse the city with meaning.

In his address to students in Copley Formal Lounge, Sheldrake described cities as full of spiritual places, where people come together to create shared histories, memories, and meanings as they traverse through the stages of life. Though Sheldrake employs the vocabulary and imagery of Christian theology, his ideas are, at their core, inclusive, egalitarian and universal in scope, ultimately transcending any one religious tradition.

The “sacred,” for Sheldrake is, in his own words, “not necessarily a ‘religious’ term, but a term that refers simply to humans’ highest aspirations and shared visions.” The sacred can be found in those “opportunities for human enhancement through human interaction,” which city spaces can and should cultivate. According to Sheldrake, cities become platforms upon which humanity’s shared visions and aspirations can be realized, which Sheldrake more fully explores in his numerous writings and scholarship.

The son of a practicing Roman Catholic mother and a non-practicing Anglican father, Sheldrake spent the first eighteen years of his life in Bournemouth, a small, beach-lined town on the southern coast of England. As a child, Sheldrake was inspired by what he refers to as an “open-minded” and “inclusive” religious experience, which encouraged him to ask hard questions and to always probe deeper.

He followed the path of becoming an ordained Jesuit priest, which took him to international universities, where he studied theology, philosophy and history. He eventually became a scholar of spirituality, the president of the International Society for the Study of Christian Spirituality, a senior research fellow at the Westcott House in the Cambridge Theological Federation, and the director of the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Spirituality at the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas. These experiences exposed Sheldrake to a variety of cities, big and small, around the world, but also cultivated in him “a sense of displacement” and the profound meaning that places can take on once one is separated from them.

His love and interest for cities was nurtured at every step. Sheldrake links his fascination with place to his childhood experiences living with the sea, which evoked a sense of the sacred to him; as well as to the death of his father, which led to his family’s displacement from his idyllic childhood home. Only later in life, while living abroad in India, a culture and context entirely foreign to him, did he start to consider the significance of space and places in his own personal life journey.

He started to more deeply appreciate that individual places take on meanings to those who live and commune there due to a variety of complex forces and factors. Through shared memories and stories, which are passed down from one generation to the next, and through shared spaces, where people converge to exchange their daily musings, individual places in cities embody a unique cultural construct.

According to Sheldrake, when reflecting on the evolving city, what matters above all is to improve the human experience of people’s lives, not “bulldozers,” new buildings or capital improvement plans. Cities provide shared spaces for residents to come together and to create, exchange, and then pass on, “shared narratives and meanings.” The unspoken rules of social organization make communities meaningful, or as he says, “sacred.”

To illustrate this concept, Sheldrake shared the story of his cousin, whose family lives in a historically marginalized and industrial city in northern England. This city became the site of a massive redevelopment project and was transformed into a sea of modern high rises and material “improvements.” The city’s apparent blight was largely eliminated and most of the inhabitants were relocated to objectively cleaner and more modern, spacious apartments. Yet, a feeling of nostalgia and longing for the city has spread among the inhabitants, including Sheldrake’s cousin, who would have happily traded his modern amenities for the shared spaces and meanings that infused the now erased city.

As a contemporary urbanist who speaks fearlessly in the language of theology, morals and values, Sheldrake seeks to find ways that cities can intentionally become sacred. Despite his infectious optimism, Sheldrake is not naïve; he understands the enormous challenges and divisiveness that plague many of the world’s cities and worries about the practicalities of implementing his utopian vision on the ground. Yet, he remains hopeful and undaunted, and feels strongly that striving towards the common good can have profound practical implications for city planners and community builders, so long as it is understood that this vision must, first and foremost, be driven by and for people.

In an open dialogue with Bryan McCann (Professor and Chair, History Department), Shareen Joshi (Assistant Professor, School of Foreign Service); and Uwe Brandes (Faculty Director, Global Cities Initiative), Sheldrake emphasized the deep traditions of humanism in the urban context. In a session entitled, “Why We Need the Humanities to Understand Global Cities,” the dialogue spanned Rio, Jaipur, London and Washington, D.C. as places which require the employment of the humanities in order to decipher the complex and rapidly changing social dynamics of place-bound economies and community networks.

The Global Cities Initiative is grateful to Professor Sheldrake for his time, efforts and enlightening insights he shared with students and faculty during his week at Georgetown. Professor Sheldrake will be returning to campus again in February 2019.

Chrystie Flournoy Swiney, JD, PhD ABD, is a human rights attorney and doctoral candidate in the Government Department; she serves as research fellow for the Global Cities Initiative.